Brief History of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

The origins of Traditional Chinese Medicine have been lost in prehistory, a time before writing was invented. The Chinese Civilization, being over 5000 years old, can trace back writings on medicine that are approximately 2000 years old, which makes TCM the oldest holistic (treatment of the whole person, including mental and social factors) medical system in the world. Although there are many theories on the origins of TCM, they cannot be proven. We do know that it is heavily rooted in Eastern philosophies such as Taoism and Confucianism. The essential philosophical principle in TCM is the movement of Qi (life force or spiritual energy) as the result of the constant dynamics between the yin (femininity, inertia or death) and the yang (masculinity, positive side of emotions or life) (Korbe 356).

Early Immigrant Healthcare in Canada

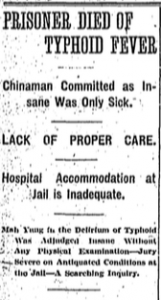

From the 1880s, Chinese labourers that toiled on the Canadian Pacific Railway died of accidents, illness and malnutrition, and in addition to the dismal conditions they were forced to live in, there were no doctors available to treat them (Lai 32). 1923 to 1947 also constituted the period of Chinese exclusion, where the Chinese were not only barred from entering Canada, but the ones who lived here were denied many civil rights. The exclusion had a serious economic impact on the Chinese, as they were denied basic rights, and were also disadvantaged in the labour market, rendering their ability to earn a living in jeopardy. Lack of medicare, and the scarcity of doctors everywhere in Canada made life very difficult for the sick (Li 47).

TCM in Chinatown

Access to hospitals in Old Chinatown, especially during the early settlement years, was very limited. Not only were hospitals scarce everywhere in Canada, but a language barrier as well as an underlying fear of racism during that time that prevented many Chinese from seeking occidental medical treatment. Trust, then, was put in traditional medicines, as it was easily accessible, particularly to the elders who, in Chinese culture, disliked being a “burden” on their family. TCM allowed the avoidance of requesting family assistance as well as a way to pass down knowledge and cultural heritage (Kong and Hseih 841-849).

Early Perception of TCM Doctors

Compared to other occupations held by the Chinese in Old Chinatown, Chinese doctors and herbalists were surprisingly respected and among the best educated of all immigrants. They were also the mostly likely to forge ties with Euro-Canadians and other non-Chinese communities. The first half of the twentieth century also saw Chinese consumer goods available in mass markets, world fairs, and traveling shows that popularized “Orientalized” arts and ideas. Although the “exoticism” of TCM made it desired, it was also seen as an inferior practice by those who were opposed to “progress”, such as the Women’s Rights Movement, which was underway at that time. Heightening anxieties and reservations about TCM and other movements led to a belief in some that because TCM was “deviant”, their patients, who were mainly women, were too (Shelton 265).

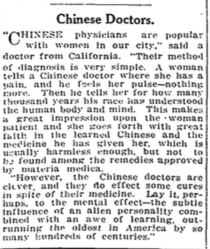

Women were especially interested in TCM as it was non-invasive:

“Women and Chinese Doctors” Source: “Chinese Doctors.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971): 17. May 10 1912. ProQuest. Web. 10 March 2015.

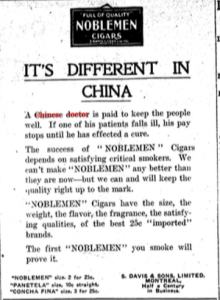

Chinese doctors were often cited as a source of authority in advertising:

“Chinese Doctors in advertising Cigars” Source: “It’s Different in China.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971): 12. Dec 24 1909. ProQuest. Web. 10 March 2015.

“Chinese Doctors in advertising for Watchmen” Source: “A Personal Watchman – at your service.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971): 18. Nov 23 1927. ProQuest. Web. 10 March 2015.

Chinese doctors were also used as a source of respect and wisdom in occidental health issues:

Respect for Chinese Doctors as Illuminating Source: “Oculist May Detect High Blood Pressure.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971): 1. Jun 06 1918. ProQuest. Web. 10 March 2015.

continued… Source: “Oculist May Detect High Blood Pressure.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971): 1. Jun 06 1918. ProQuest. Web. 10 March 2015.

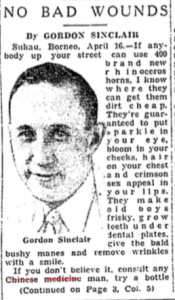

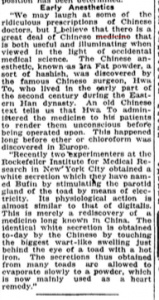

Many positive articles about Chinese doctors spoke of the merits of the practice:

TCM Today

The 1970s saw improved foreign relations with China, which also resulted in the embracement of Eastern philosophies and practices, especially acupuncture. In the 1980s to the 90s, schools for “Oriental” medicine began to open and in 1994, US Congress decided to exempt herbal remedies from FDA regulation. In addition to this, the National Institute of Health established a permanent study for “alternative medicine”, which included Chinese medicine (Shelton 265). In Canada, acupuncture is now regulated, and TCM is taught at accredited institutions such as the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (Ma 181). Initially spread by word of mouth and through family, TCM has become increasingly more popular for its natural qualities and the decrease in dependence on medical pills, which cause many side effects. In today’s consumerist and narcissistic society, there is so much emphasis on youth and beauty with an eager willingness to try out anything “new”. There is a great interest in health and well-being for not only the body, but the spirit as well (Korbe 365-366). The many TCM clinics and herbal remedy stores that are not just confined to Chinatown anymore, have become the “biggest aspect of Chinese culture that has gained mainstream acceptance in Canada” (Ma 181) after Chinese cuisine.

Bibliography

Kong, Haiying and Elaine Hsieh. “The Social Meanings of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Elderly Chinese Immigrants’ Health Practice in the United States.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 14.5 (2012): 841-849. Web. 14 July 2015.

Korbe, Merit. “Chinese Medicine in an Occidental Perspective.” Asia Europe Journal 6.2 (2008): 355-358. Web. 14 July 2015.

Li, Peter S. Chinese in Canada. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1998. Print.

Lai, David Chuenyan. Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1998. Print.

Ma, Adrian. How the Chinese Created Canada. Edmonton: Dragon Hill Pub., 2010. Print.

Shelton, Tamara Venit. “Curiosity or Cure? Chinese Medicine and American Orientalism in Progressive Era California and Oregon.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 114.3 (2013): 265. Web. 14 July 2015.

Image Sources

“A Personal Watchman – at your service.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 23 Nov. 1927: 18. ProQuest. Web. 10 March 2015.

“Chinese Doctors.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 10 May 1912: 17. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

“Doctors Re-Discover Remedies — Bride Broder.” The Globe and Mail (1936 – Current) 16 May 1938: 14. ProQuest. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

“It’s Different in China.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 24 Dec. 1909: 12. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

“No Bad Wounds.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 27 May 1933: 1. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

”Oculist May Detect High Blood Pressure.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 6 June 1918: 1. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

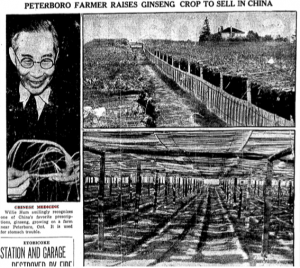

“Peterborough Farmer Raises Ginseng Crop to Sell in China.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 2 Nov. 1938: 6. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

“Prisoner Died of Typhoid Fever.” The Globe (1844 – 1936) 25 Mar 1910: 8. ProQuest. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

“The Chinese Pioneer in Many Inventions: Early Aesthetics.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 21 Feb. 1924: 3. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

”Treatment Requests Flood Chinese Doctor.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 20 Feb. 1943: 22. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

Contributor’s Bio

Mona Ilahie is a second year English major in the Faculty of Arts program at Ryerson University with a previous degree in Business Management. An aspring novelist who loves reading and traveling, she hopes to one day write about her global experiences.