Chinese Schools in Canada

Chinese schools initially began to exist in British Columbia in the late 1800’s, Chinese children needed schooling and were not welcome in white public schools. This was because many white parents did not want to integrate the Chinese children with their own. This caused the Chinese communities to need their own educational spaces. In British Columbia there were various laws passed to prevent Chinese children from attending public schools such as passing an English language test that was not required for any white immigrants.

Chinese parents argued that their children would be able to learn Canadian culture better within public schools but with constricting laws it became easier for Chinese parents to keep their children in Chinese schools. It took until the 1920’s for Chinese children to be able to attend public schools, at this point Chinese schools were used as a more recreational form of learning Chinese culture.

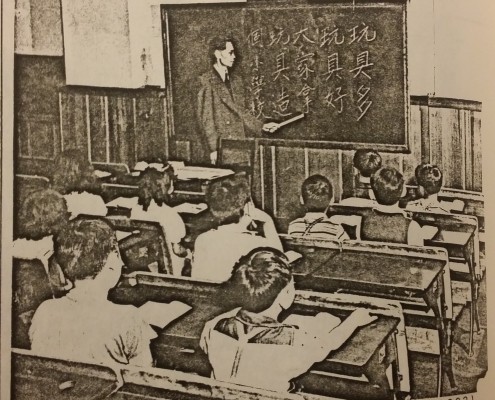

The purpose of Chinese Schools began to change and the Chinese used them to make sure their children were learning language, geography and culture. The schooling followed a classic model such as how schooling was performed in China. This model persisted for much longer than expected. The schools first began to exist in British Columbia in the late 1800’s and grew from there. By the 1950’s Chinese schools were beginning to appear more frequently in Toronto in church basements. Some common ones at the time were Chinese Presbyterian Church (now the Markham Chinese Presbyterian Church) and Mon Sheong Foundation Chinese School which started classes in 1968.

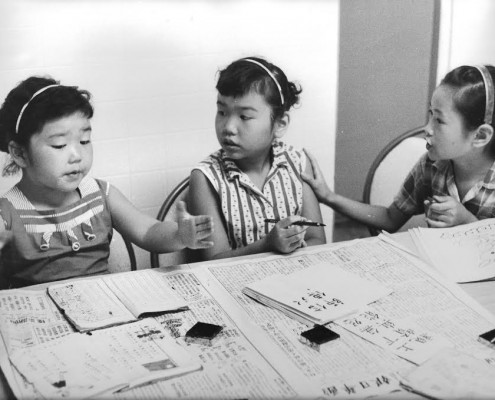

Chinese Schools have increased in popularity in recent years with many schools offering after school programs as well as external schools still existing and operating out of churches or their own locations across Toronto. Many Chinese families see these schools as an opportunity to have their children learn Chinese, culture, holidays and traditions. The children who attend are often first generation or beyond, their parents using Chinese school as a way for their children to connect with other Chinese-Canadian children while being able to learn about their history and culture. Chinese schools have updated their curriculums from their inception and allow for better language lessons and better understanding of the classes.

Children who attend Chinese School are given the opportunity to connect with a culture that they would otherwise have difficulty understanding. They are also seen as a way that Chinese children can attend school as majority rather than a minority, allowing their voices to be heard and interact with other Chinese children without discrimination. Within public schools Chinese-Canadian children experience a series of systematic racial issues such a being ignored in the class, being bullied, being treated poorly, microaggressions from both teachers and other students.

“I went [to Chinese school] from 1958 for five years… So I started as an eight year old and went until I was in grade eight. I always complained to my parents, I said you know when I think about all the hours that I sent – because if you do five days and meet two hours from September till June for that many years, five years, that’s a lot of hours of instruction… All that time I spent in Chinese school we really could’ve learned so much more if the teaching had been more modern or more relevant, like teach us how to speak, we never spoke, we never learned like to speak – like how we go to a restaurant, go to a store and order things…. My parents didn’t have time to tutor us because they were both working first at the grocery store like long hours and then afterwards working at the restaurant too, so. So I understood that, but I still don’t have the best memories of Chinese school.”

“So we had to sit on the streetcar for an hour to get to Chinese school which was from 5 until 7 o’clock and we did that every day from Monday to Friday.”

Following the hours at daytime school Chinese-Canadian students would travel to their Chinese school. Chinese school would take place for two hours, making a Chinese-Canadian child have 8 hours of public school followed by an additional 2 hours of Chinese School. Including travel time of about one hour on the streetcar each way these students often experienced 12 hour days of schooling.

“We really learned not a lot because it was a very traditional Chinese traditional style of teaching”

Despite parents wishes Chinese schools were often seen as unnecessary by their children. The textbooks were from Taiwan and completely outdated.The language taught was outdated, there was not enough emphasis on the cultural practices and the teaching style was so strict that it was a dreaded experience.

“we also learned how to do Chinese calligraphy using a brush and – which was something that was very useful because the Chinese language is very complicated, and when you see a Chinese character, there’s a very strict way as to how you write the strokes and in what order and from left to write and from the top to the bottom, and all those rules.”

If the students faltered on their lessons they would be smacked on their knuckles with a ruler. Chinese school was one of the few ways to receive these lessons, otherwise parents would have to hire a private tutor.

“It was so strict about learning like Chinese poetry, Chinese geography, history, and nothing that talked about Canada”

Chinese school was not seen as beneficial to the students, merely a required time commitment. Despite parents efforts, students often found that they learned more practically things such as language working in the Chinese restaurants rather than attending school. In the end, Chinese school was remembered as a horrible experience.

Chinese school has progressed in fascinating ways since its’ inception. Beginning as a way for Chinese parents to assure their children received education and progressing to become a way to assure that the children of Chinese immigrants would learn language, geography, culture as well as experience school with other Chinese-Canadian children. Chinese schools, though not the best experience in the past, are now seen as great ways for Chinese-Canadian children to experience their culture.

-

Chinese Presbyterian Church. 1957. Multicultural History Society of Ontario, Toronto. Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Web. 13 July 2015.

-

Cui, Dan. “Two Multicultural Debates and the Lived Experiences of Chinese-Canadian Youth.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 43.3 (2011): 123-43. Print.

-

Hirata, Lucie Cheng. “Youth, Parents, and Teachers in Chinatown: A Triadic Framework of Minority Socialization.” Urban Education 10.3 (1975): 279-96. Print.

-

Lai, David Chuenyan. Chinese Community Leadership: Case Study of Victoria in Canada. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co., 2010. Print.

-

Lai, David Chuenyan. “The Issue of Discrimination in Education in Victoria, 1901-1923.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 19:3 (1987): 47-76. Web. 13 July 2015.

-

Teachers and students at the Chinese Public School. 1913. Photograph. Victoria’s Chinatown. University of Victoria, n.d. Web. 13 July 2015.

-

Wickberg, Edgar. From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982. Print.

-

Wong, Kileasa Che Wan. “History and Significance of the Victoria Chinese Public School, Huaqiao Gongli Xuexiao, 1899-1999.” University of Victoria, 1999. Web. 13 July 2015.

-

Yeh, Diana. “Contesting the ‘model Minority’: Racialization, Youth Culture and ‘British Chinese’/‘Oriental’ Nights.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37.7 (2014): 1197-210. Print.