Battleship Arizona burning and settled on the bottom as seen from Ford Island, Pearl Harbor. Comp. Peter Chen. 1941. Photograph. World War II Database. Lava Development, LLC, n.d. Web. 16 July 2015.

On December 7th, 1941 Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Approximately 8 hours later Japanese forces invaded and eventually captured the city of Hong Kong, which at the time was under the control of the British. These two actions would set into motion what we now call the Pacific Theater of World War II, which was fought between the western allies and those who sided with Japan. The other thing that these events would set off would be the acceptance of Chinese immigrants into Canadian culture. However this would take much, much longer. In fact it would take longer than the war itself.

The Battle of Imphal-Kohima March – July 1944: The remains of Japanese dead, equipment and caved-in bunkers on ‘Scraggy Hill’ which was captured by 10th Gurkha rifles in fierce fighting in the Shenam area. Ed. Martin Cherrett. 1944. Photograph. World War II Today. World War II Today, n.d. Web. 16 July 2015.

In 1942 the Burma Campaign began. Many Chinese-Canadians who volunteered were sent to this campaign due to them being able to easily translate between English and Chinese Languages. This was another important moment in Chinese-Canadian history, as not many regiments were accepting of Chinese soldiers. In fact the Royal Canadian Air Force only allowed Chinese-Canadians in October of that year. The Burma Campaign was a chance for Chinese- Canadians to show not just Canada, but the world, their worth. This, in turn, began to shape Canadian society’s perspective on Chinese immigrants. This can be seen through publications like:

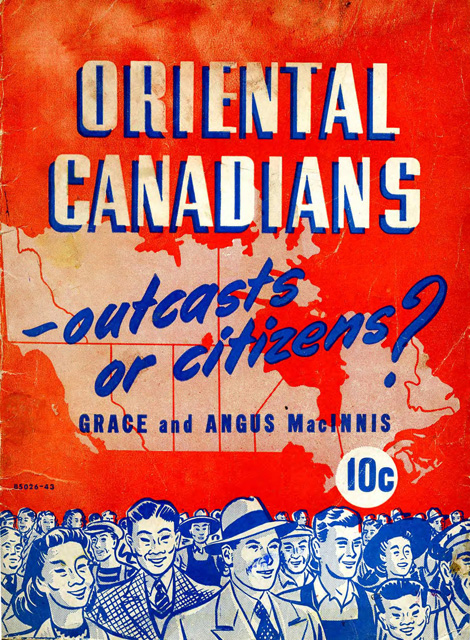

MacInnis, Grace and Angus MacInnis. Oriental Canadians, Outcasts or Citizens? book cover. MacInnis, Grace and Angus MacInnis. Oriental Canadians, Outcasts or Citizens? book cover. Vancouver: Federationist Publishing Co., 1943. Simon Fraser University Library. Web. 16 July 2015.

The pamphlet, Oriental Canadians: Outcasts or Citizens? shown above is an example of the changing national perspective on how Chinese-Canadians should be treated. Notice now “China man” is unused in the pamphlet, and how the people shown are not stereotypical caricatures of their race.

The pamphlet was printed in 1943, and calls for awareness and justice for social minorities, focusing mainly on Chinese-Canadians. This shows that the public opinion was beginning to change, and this change was sped with the Conscription Crisis of 1944.

William Mackenzie King voting in the plebiscite on the introduction of conscription for overseas military service. 1942. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 16 July 2015.

In 1943-44, prior to D-day, Canada faced a shortage of volunteer soldiers, and began to enforce conscription for the first time since World War I. This, along with the need for those who could speak the languages spoken in China, caused an amendment to the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) wherein the federal government was allowed called upon Chinese immigrants to volunteer for the war effort.

Many in the Chinese community opposed going to war, as volunteering was seen as something only citizens of Canada were expected to do, and that they were not treated like citizens in the first place. Town meeting were held, and the Chinese community came to the conclusion that joining the war effort would allow them a chance to franchise, and, eventually, become official citizens of Canada.

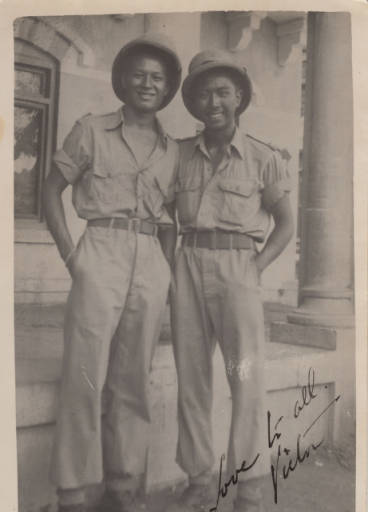

Victor E Wong and a comrade, both part of Special force 136. N.d. University of Victoria, Victoria. University of Victoria Digital Collections. Web. 16 July 2015.

Roughly 600 Chinese-Canadians Volunteered. Victor E. Wong was one of that number.

Victor Wong, in the audio post above, discusses racial discrimination in Canada, as well as the reasoning behind why Chinese-Canadians decided to join the war effort.

After the war ended, and the Chinese-Canadians returned with the rest of the troops, calls from both the Chinese community and the public pressured the government to make changes to Chinese related immigration laws. First, the Exclusion Act was repealed on 14 May 1947, meaning that Chinese were finally able to immigrate to Canada without specific titles, for the first time since 1923. Though there were restrictions, this was an obvious crack in the wall that closed the west off from China. Later in 1947, Chinese Immigrants were granted the federal franchise, and in 1949, they were finally given the right to vote in provincial and municipal elections.

These were the medals given to Victor Wong for his participation in World War II. 2011. University of Victoria, Victoria. University of Victoria Digital Collections. Web. 16 July 2015.

The veterans return from World War II was the beginning of the end of Chinese exclusion in Canada. If Canada had awarded them for their help in World War II, but not given them citizenship, the public and international outcry would have been immense. Though the public was not “cured” of the racism that was ingrained in Canadian society by it’s exclusionary laws, the Chinese-Canadians who fought and helped with the war effort helped the Chinese community grow and flourish in Canada. Without them, the Chinatown we know today would never have existed.