The Rise and Fall of Toronto’s First Chinatown: 1878 – 1960

Toronto is a city of many Chinatowns — both within the boundaries of the city proper and in the Greater Toronto Area. The first area to be known as Chinatown was located in downtown Toronto primarily in “The Ward” (along Elizabeth Street), an area known as a starting point for many immigrants to the city. This original Chinatown was destroyed when its properties and land were expropriated to build new City Hall in the mid 1960s. In the winter 2015 term, Ryerson University students in ENG 390 explored the idea of “Chinatown” as a literary concept and traced the rise and fall of Toronto’s original Chinatown by researching and creating a timeline. The timeline begins in 1878, the year the first Chinese person was recorded in Toronto, and ends in 1960, prior to the completion of new City Hall. It covers events that would have impacted on, or have been of interest to, the Chinese community in Toronto (and in Canada) during this period.

Throughout the semester, students tracked their research progress on a class blog located at: http://eng390w15al01.blog.ryerson.ca/. The blog provides additional information and images surrounding the Rise and Fall of Toronto’s original Chinatown.

1878

The Federal Election

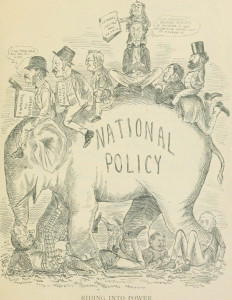

With the election of Sir John A. Macdonald as Prime Minister, came the enactment of the National Policy — high tariffs on foreign goods to protect Canadian manufacturers. The National Policy later became a centrepiece of the Conservative Party.

John Wilson Bengough, cartoonist of The Grip magazine created this cartoon, “Riding Into Power” to embarrass the Tories, as he believed that a white elephant with all white political riders, crushing opponents and free trade would be shameful. It backfired however, as the elephant looks strong and unstoppable, positively crushing opponents.

Image Source:

Bengough, John Wilson. Riding Into Power. 1886. McCord Museum, Montreal. McCord Museum. Web. 26 June 2015.

1878

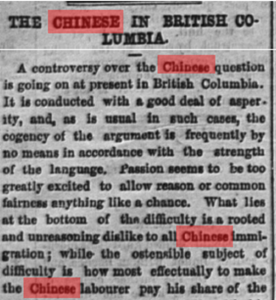

The Chinese Question

August 26, 1878: An article is posted in The Globe and Mail, debating how to tax the Chinese immigrants in British Columbia since many citizens do not think it is “necessary to impose either a special immigration or poll tax on a particular class”. This article shows a more sympathetic side of those living in B.C. towards the Chinese. It still uses such language as “mean” and “bad habits”, to describe the Chinese, however, it is not completely condemning the Chinese immigrants, compared to others.

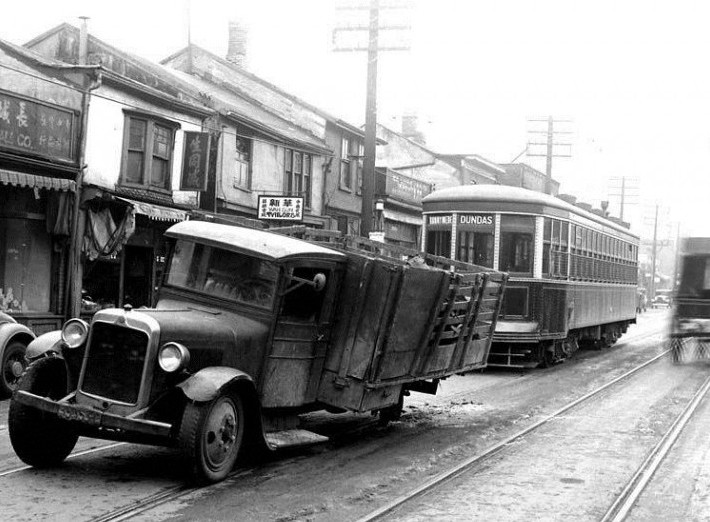

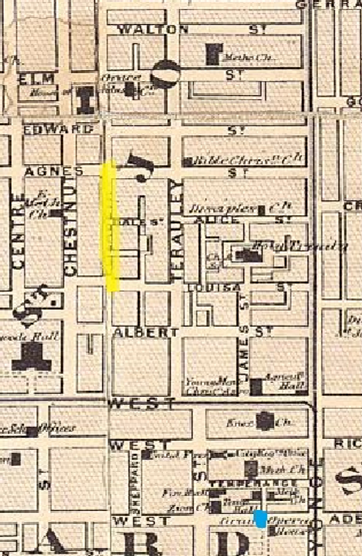

While much development was happening around the country, Toronto’s Chinatown was just beginning. These maps of Toronto, display Sam Ching’s (first Chinese man recorded in Toronto) laundry on Adelaide and the Old Chinatown on Elizabeth Street.

Image Sources:

Cotterell, A.T. “Illustrated Historical Atlas of the County of York.” 1878. Digital image. Historical Maps of Toronto. Web. 26 June 2015.

Cotterell, A.T. “Map of Toronto.” 1878. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Historical Maps of Toronto. Web. 16 July 2015.

“The Chinese In British Columbia.” The Globe (1844-1936) 26 Aug. 1878: 2. Proquest. Web. 29 June 2015.

1879

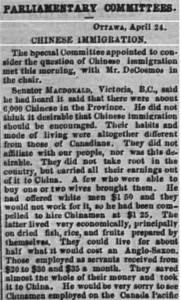

Thoughts on Chinese Immigration

April 24, 1879: The Globe And Mail publishes a piece on Chinese immigration, writing that of the speculated 6,000 Chinese immigrants in the country, Senator Macdonald of B.C, “did not think it desirable that Chinese immigration should be encouraged.”

Image Source:

“Parliamentary Committees: Chinese Immigration.” The Globe (1844-1936) 25 Apr. 1879: 4. Proquest. Web. 29 June 2015.

1881

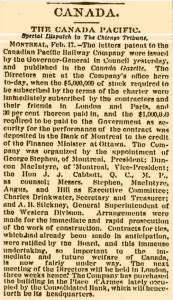

Incorporation of the CPR

February 17, 1881: The Chicago Tribune reports that “Letters patent to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company were issued.” This meant that the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway could begin. The construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway was one of the conditions under which British Columbia entered into Confederation (the union of The British North American colonies).

The completion of the railway would connect East and West Canada, and would help to develop the country. According to this article, the cost of the railway would be $5,000,000 worth of stock and $1,000,000 required to be paid to the Government. But that was just the beginning. It is believed that the railway cost approximately $37 million.

With plans for how to pay for the railway up in the air, Chinese immigrants from the U.S. and later, directly from Hong Kong, were brought in as cheap labour to build the railway.

Between 1880 and 1881, 1500 Chinese workers were hired from San Francisco through the services of the Lian Chang Company. They were sent to British Columbia to construct the railway. Lian Chang and other companies brought workers straight from Hong Kong in 1882 to help complete the railway. The workers were mistreated by those living in B.C and the working conditions were horrendous. It is estimated that at least 600 workers were killed during the construction.

Image Sources:

“The Canada Pacific.” The Chicago Daily Tribune 18 Feb. 1881: 5. Chicago Tribune Archives. Web. 29 June 2015.

VPL # 421; C.P.R. Wooden Bridge Over Skuzzy River. 1881. Vancouver Public Library, Vancouver. Canadian Pacific Railway Photograph Collection. Web. 29 June 2015.

1882

Toggle Content goes here

1883

Toggle Content goes here

1884

Toggle Content goes here

1885

Toggle Content goes here

1886

Mob Violence against the Chinese

In 1886, after the Canadian Pacific Railway was officially completed, thousands of Chinese immigrants were stranded without any work. Many of them moved to Vancouver to find jobs, while some left for San Francisco. In January of 1886, Chinese immigrants were camped on the shore the Vancouver Harbour. They were hired to clear trees and stumps at a severely reduced pay, compared to what the white workers would have been making. An angry mob of out of work, hungry citizens stormed the Chinese camp in the west end at night and assaulted the Chinese. There were no deaths, but many injuries.

Image Source:

Deville, Edouard. Chinese Workers’ Camp on the C.P.R. C-021990. 1886. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. The Critical Thinking Consortium. Web. 29 June 2015.

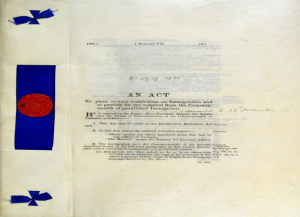

1887

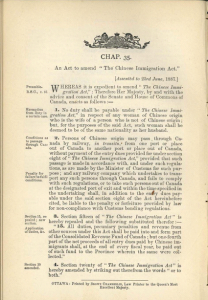

Chinese Immigration Act Amended

In 1887, amendments to the Chinese Immigration Act expanded the list of people who were exempted from the Act. Chinese individuals passing through Canada via railway were also exempt from the Head Tax. A discounted service made it extremely easy for Chinese workers to travel farther east and served as a strong incentive to leave the west coast.

Image Source:

“An Act to Amend ‘The Chinese Immigration Act.’” 1987. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21.Statutes of Canada, n.d. Web. 30 June 2015.

1888

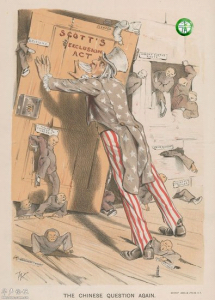

Restrictive and Exclusionary Legislation

One would think that these scores of Chinese men would try to make their way to America from Canada after the completion of the CPR, but in 1888, America passed The Scott Act. The law prohibited the immigration of virtually all Chinese people by effectively rescinding certificates of re-entry for any Chinese abroad for twenty years. This stipulation would apply to all unless they had assets worth at least $1,000 or immediate family living in America. The Scott Act was introduced as a sort of companion piece of legislation to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The result of this law left about 20,000 – 30,000 Chinese immigrants stranded just outside the US.

Within that same year, a similar bill was drafted in Australia entitled The Chinese Restriction and Regulation Act. The Bill was primarily drafted for the express purpose of arresting the flow of Chinese immigration due to the gold rush at the time. The Bill tried to disallow the immigration of Chinese workers through the technicalities of bureaucracy as opposed to outright measures. For example, one stipulation of the Bill stated that one Chinese male was permitted to enter Australia per every 300 tonnes of the vessel carrying him. The Bill also increased the poll tax to £100. The Bill also effectively ended the practise of exemption certificates within Australia, which made it incredibly difficult for any Chinese immigrant to possess the correct papers to enter Australia legally.

Image Sources:

Keller, George F. “The Chinese Question Again.” The San Francisco Wasp 28 Feb. 1888. American Memory. Web. 29 June 2015.

Statues of Australia. Chinese Restrictions and Regulations Act, 1888. Victoria, Chapter 4. Web. 12 July 2015.

1889

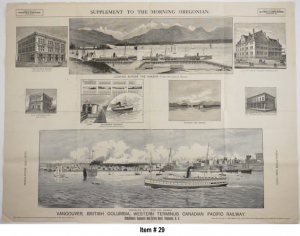

Railway Lines in the East

In 1887, the Canadian Pacific Railway moved its terminus from Port Moody to Vancouver. The railway was quickly profitable and paid back its loans from the Federal Government years ahead of schedule. As a result, the success of the CPR bolstered confidence in the government to green light an additional branch line between Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie, where Canada connects to the US railway. Within the same year, work began on a line from London, Ontario, to the American border at Windsor, Ontario, which opened on 12 June 1889. The connection of the additional terminals and the expansion of the CPR lines farther east allowed Chinese immigrants to move east, away from the social upheaval in the west coast. This is not to suggest that Toronto itself was free from racism or discrimination, but simply suggests that the forms of oppression that existed in other parts of Canada provided an environment that help foster the coming-into-being of Toronto’s ‘Chinatown’.

Image Source:

Pickett, J. “Vancouver, British Columbia, Western Terminus Canadian Pacific Railway.” Photograph. The Wayfarers Book Shop. The Wayfarers Book Shop, 1 Jan. 2012. Web. 19 Mar. 2014.

1890

Protestant Mission Schools in Victoria, BC

Image Source:

Chinese Canadians at the Mission School in Vancouver, B.C. in 1898. 1898. Vancouver Public Library, Vancouver. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Web. 30 June 2015.

1891

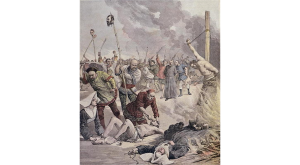

Anti-Foreign Riots in China

In 1891, a series of riots broke out in China, starting in the Yangtze valley, and extended throughout the empire for ten months. Missionaries and Christians (both foreign and native) were targeted the most severely; their lives were threatened, their houses were burned, and many native Christians were massacred. It is believed that the causes of these riots were a combination of factors including, government incapacity, the threat of Christianity (overtaking Chinese traditions), opium sales, colonization, etc., all of which would have caused a great deal of hostility towards foreigners during the time.

Image Sources:

“Christians in China being Tortured and Murdered During the Boxer Rebellion (1900).” Digital image. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Anti-Christian Comic Has a Moral (反洋教漫画 有寓意).” Digital image. Shezhuzhanyang FIG (射猪斩羊图). Historical Perspectives (历史大视野), 5 June 2015. Web. 12 July 2015.

1892

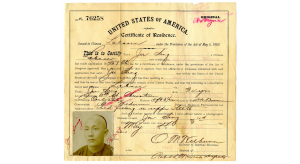

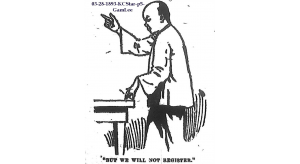

Zhi Gong Tang Political Association Established and Anti-Chinese legislation in the US

Image Sources:

Advertisement Released around the time of Amendments to the Geary Act. The Internet Web Log of Jesse La Tour. Blogger, 27 Mar. 2013. Web. 6 July 2015.

“But We Will Not Register.” Digital image. Kansas City Stories 1893. Kansas City Stories 1893, n.d. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Certificate of Residence.” 1892. California Historical Society, San Francisco. Online Archive of California. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Qing Dynasty (1892).” Digital image. “Atlas of the People’s Republic of China.” Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia, 6 Mar. 2015. Web. 6 July 2015.

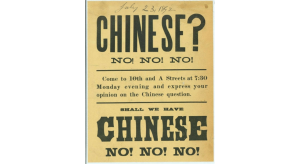

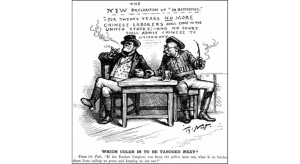

1893

The McCreary Act Passed in the United States

Image Sources:

Nast, Thomas. Which Color is to be Tabooed Next?. 1882. Harper’s Weekly, New York. Thomas Nast Cartoons. WordPress. Web. 30 June 2015.

“The McCreary Act Passed.” San Francisco Call 17 Oct. 1893: 6. California Digital Newspaper Collection. Web. 29 June 2015.

1894

First Sino-Japanese War Begins

On August 1st, 1894, the first Sino-Japanese war began. The war was over who would have primary control over Korea (at that time, Korea was a Chinese state).

1895

The Qing Dynasty sued for peace in February of 1895. The Treaty of Shimonoseki forced China to recognize the independence of Korea and pay war debts back to Japan. The Japanese won the war for many reasons, some of which included a greater level of modernization and industrialization. Corruption and a lack of moral for many reasons, such as pay and poor leadership, negatively impacted the Chinese during the war.

The Sino-Japanese war was a contributing factor in Chinese migration to Canada. The war caused some Chinese to lose faith in their government and they sought out another home for themselves.

Image Source:

Kenshin, Ozawa. Bakumatsu Meiji no Shashin. 1894. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 29 June 2015.

1896

The Visit of Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang was an important statesman, diplomat and military leader in China. He came to visit Canada in 1896, as part of a world trip that he was encouraged to take after falling into poor favour in China because of China’s losses in the First Sino Japanese war. Hongzhang was the first major political figure from China to come to Canada,

Hongzhang traveled from England, made a brief stop in Toronto before his big welcome in Vancouver. Representatives from all over North America, from as far as Seattle, Portland and San Francisco (6,000 people), came out to welcome him.

The Chinese in Canada appealed to Hongzhang to enter into discussions with the Canadian government over the head tax. Hongzhang did pursue this matter and through his representation may have stalled the proposed increase in the head tax at that time.

Hongzhang’s visit was an important event for the Chinese Community in Canada. His visit showed the Chinese in Canada that they were not forgotten in their homeland and that China still cared for their people whether they were at home or abroad.

Image Source:

Hongzhang, Li. Li Hongzhang State Visit to Canada. 1896. Photograph. China’s External Relations – A History. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 June 2015.

1897

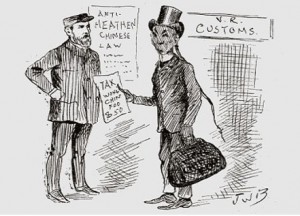

Head Tax Introduced

The Chinese Immigration Act stipulated that all Chinese people who immigrated to Canada had to pay a $50 tax per person. This tax was created in the hopes that it would discourage any more Chinese people and their families from coming to Canada as the cost of the tax created great financial hardship for the Chinese. The head tax was only imposed on the Chinese immigrants of Canada.

Around 1,762 people (including Lem Wong, a well-known figure in the Chinese community in Toronto who disputed the tax) paid the $50 dollar head tax. The money from the head tax collectively generated $88,000 in taxes for the for federal coffers.

Image Source:

Bengough, John Willson. Wong’s Dispute with the Canadian Government over Payment of a $50 Head Tax. Digital image. The First Chinese American. Scott D. Seligman. Hong Kong University Press, n.d. Web. 30 June 2015.

1900

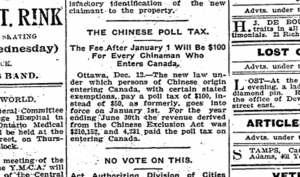

The Head Tax Increased and the Boxer Rebellion

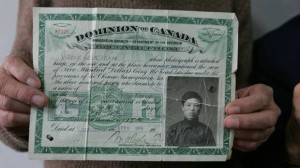

In 1900, the head tax was raised to $100. Chinese immigrants were given a certificate which contained information such as their name, photo, a description of their appearance, their intention for being in Canada, and destination. In theory, the doubling of the head tax amount should have played a large part in hindering Chinese immigration to Canada. As we know, this did not completely stop the Chinese from immigrating. This is seen through the later increasing of the head tax to $500, as well as the later Chinese Exclusion Act. The continued attempts to bar Chinese entry to Canada raises the important question: what was going on in other areas of the world for there to have been such a strong desire for Chinese peoples to leave their home land and try to enter Canada?

One contributing factor to Chinese migration to Canada may have been a rebellion that was going on throughout China in 1900. Known as the “Boxer Rebellion”, the Yihequan (a secret society in China) was attempting to rid China of Western influence by driving foreigners from China. The Yihequan (which translates as “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”) believed that Westerners residing in China had a privileged position which they resented. Their ultimate goal was, however the destruction of the ruling Chinese dynasty.

Image Sources:

“Boxer Rebellion – Chinese History.” Digital image. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

“The Chinese Poll Tax.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 12 Dec. 1900: 3. Proquest. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

1901

“White Australia” Policy

In 1901, the Australian Immigration Restriction Act, also known as the “White Australian Policy,” was established with the goal of stopping the Chinese from immigrating. A wide concern for those in power in Australia was that there was a continuing growth of coloured immigration, hindering their desire for a white community. The Act was, however, created particularly with immigrants of Asian descent in mind. Under the provisions of the Act, non-European people wishing to enter Australia had to take a dictation test, which could be performed in any European language. The Act may have been one of the reasons that immigration continued to Canada despite the increase of the head tax in 1900. It was now exceedingly difficult for a Chinese person to to immigrate to Australia, resulting in them perhaps being more willing to raise enough money to come to Canada.

Image Source:

“Immigration Restriction Act 1901.” 1901. Digital image. National Archives of Australia. Australian Government, n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2015

1902

Head Tax Increases to $100

The Canadian Government doubled the Head Tax to $100 – and required that the Chinese leaving Canada “must return within a year of departing or face paying the Head Tax again on their return.” Later, the Head Tax would be increased to $500 — equal to two years of earnings of a Chinese labourer at the time.

Image Source:

“Taxing the Chinese.” Digital image. Road to Justice: The Legal Struggles for Equal Rights of Chinese Canadians. Metro Toronto Chinese and Southeast Asian Legal Clinic, n.d. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

1903

Head Tax Increases to $500

Following the indefinite extension of The Exclusion Act in the United State, Canada increased the Head Tax to the amount of $500 making it even more impossible for the Chinese immigrants to achieve their chance of a better life. This new Head Tax was more successful in reducing the amount of Chinese immigrants entering Canada than previously.

Image Source:

Friesen, Joe. “Chinese Head-Tax Funds Clawed Back.” The Globe and Mail 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 30 June 2015.

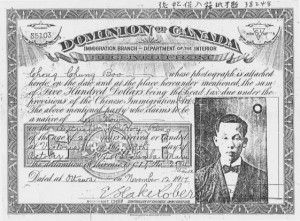

1904

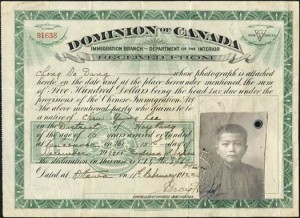

Head Tax Certificates

All immigrants that were able to pay the Head Tax were mandated to have something called a Head Tax Certificate. These Certificates were used to control and keep tabs on all the Chinese immigrants that entered Canada. In total, the Canadian Government collected around $23 million from the Chinese through the implantation of the Head Tax.

1905

Impact of the Head Tax

The Head Tax made it increasingly difficult for Chinese families to stay together. It was mostly Chinese men that were able to come over to Canada -as they were the best suited for laboring work. The cost of the Head Tax meant that their wives and children were often left behind, resulting in separations that lasted for years (sometimes, families were never reunited). Since the Chinese immigrants coming into Canada were predominantly male, the Chinese Community in Canada became known as a “bachelor society”.

1906

Opium Trade Condemned

After being pressured by the Chinese the British Parliament passed a motion condemning opium trade as morally indefensible and requested the Indian government to bring it to a speedy close all under a 3-year clause (just in case the Brits wanted to start up trade again). The evils of opium had to be eradicated within 10 years and the import of opium from India ended.

Image Source:

Zhoy, Yongming. Anti-Drug Crusades in Twentieth Century China: Nationalism, History, and State Building. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 1999. Print.

1907

Asian Exclusion League and Anti-Chinese Riot in BC

An Asian Exclusion League branch established in Vancouver on 5 of August. On Sept 7th, the Vancouver League organized an anti-Oriental parade which marched from Cambrie Street to city hall where speeches were delivered. By nightfall the crowd was at several thousand. Following this, the mob marched to Chinatown where they beat up dozens of Chinese, wrecked stores, and smashed windows.

Image Sources:

Gilmour, Julie F. Trouble on Main Street: Mackenzie King, Reason, Race, and the 1907 Vancouver Riots. Toronto: Allan Lane, 2014. Print.

King, William Lyon Mackenzie. Royal Commission Appointed to Investigate into the Losses Sustained by the Chinese Population of Vancouver, B.C. on the Occasion of the Riots in that City. Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1908. Print.

1908

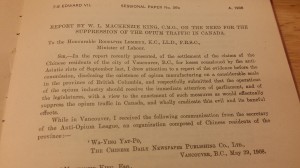

Anti-Opium League Established

The Anti-Opium League was established to petition Canadian government to stop the import of opium and outlaw its sale in Canada. Opium was officially made illegal in Canada this year.

Image Source:

King, William Lyan Mackenzie. The Need for the Supression of Opium Traffic in Canada. Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1908. Print.

1909

Opium No Longer Exported

Within China smoking opium reduced by one third in Manchuria, all but disappeared in Beijing. Shanxi closed all opium shops and wholesales, reduction from 50 to 75% in cultivation. Opium is no longer being exported from China.

Image Source:

Zhoy, Yongming. Anti-Drug Crusades in Twentieth Century China: Nationalism, History, and State Building. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 1999. Print.

1910

First Chinese Christian Church Founded in Canada

The heavy influence of Christian values in Canada led to the founding of the first Chinese Christian Church at Knox Presbyterian. The church became a place of worship as well as a place that many new Chinese Canadians went to for guidance, leadership and shelter.

Images:

Salmon, James Victor. Knox Presbyterian Church (Opened 1909), Spadina Ave. W Side of Harbord St. 1956. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 Feb. 2015.

Staples, Owen. Knox Presbyterian Church, Spadina Ave. W Side of Harbord St. 1910. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Toronto Reference Library. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

1911

First Chinese to Own Property in Toronto

The first Chinese person to own property in Toronto was a man named Mr. Gip Kan Mark who occupied property on Elizabeth St. This building was also shared by a grocer identified as Ying Chong Tai.

Image Source:

Salmon, James Victor. Elizabeth St., Looking N. from N. of Queen St.W. 1955. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 Feb. 2015.

1912

Founding of the Republic of China

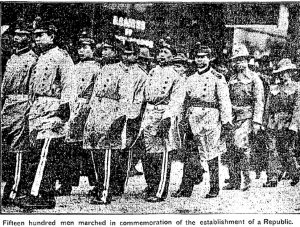

Hundreds of Chinese celebrated the founding of the Republic of China and the fall of the Chinese Dynasty at Victoria Hall. In Toronto, the Chinese held a parade which was was attended by Mayor George Geary.

Image Sources:

“A Section of Yesterday’s Chinese Parade.” The Globe (1844-1936) 9 Jan. 1912: 1. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

“In the Chinese Parade.” The Globe (1844-1936) 9 Jan. 1912: 9. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

1914

World War I Begins

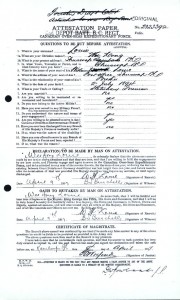

This was the year that World War I began. Chinese men were not allowed to join the army at this time, yet it did not deter them from volunteering. This is relevant and important because it shows that the Chinese really wanted to show their patriotism and loyalty to Canada. Eventually, Canada did let some Chinese partake in the battle. After the Chinese participated in this battle, some Canadians began to view the Chinese in a more positive light — although this was not enough to create significant social and political change right then and there.

Image Source:

Attestation Paper for Wee Hong Louie (AKA Walter Henry Louie). 1917. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

1915

Chinatown Expands to York Street

1915 was the year that Chinese businesses and residences began to establish themselves on York Street.

Image Source:

Chinese Residents on York Street after 1915. Photograph. Heroes of Confederation: Kamloops. The Kamloops Chinese Cultural Association, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

1917

World War I and Local Raids

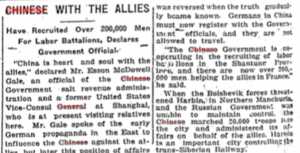

The years 1917 through 1920 marked the early settlement years of the Chinese Community in Toronto. There were many changes occurring around the world, which greatly affected the lives of the Chinese in Canada. In 1917, the First World War was still underway and Canada helped transport 80,000 men from China over the Pacific, across Canada, and then over the Atlantic Ocean to the warfront (Chan, The Chinese in Toronto from 1878, 65). The Military Service Act invoked inscription and although “Orientals” were excluded, 300 Chinese volunteered (66). Meanwhile in Canada, the Chinese population was growing and “Toronto’s Chinatown was becoming a bustling centre” (Chan, 44). Discrimination still ran rampant against the Chinese, as news articles about the vices of the “Chinamen” and “Yellow Peril” were a common occurrence (39).

Image Sources:

“20 Taken When Police Make Midnight Raid.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 12 Nov. 1917: 5. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

“Chinese with the Allies.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) Jun 6 1918: 4. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

“Six Months in Jail for Versatile Chinaman.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 24 Dec. 1917: 2. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

1918

End of World War I and Discrimination

In 1918, the Chinese community in Canada was still invested in the news about their homeland, which brought about political organizations, such as the National People’s Party (Guomintang) and the Chinese Nationalist League. That year, the Canadian government banned the Guomintang, fearing they were “violent radicals” (Chan, The Chinese in Toronto from 1878, 58). On November 11, the Great War finally ended, and despite the fact that the Chinese had been allies during the War, there was still widespread discrimination and an effort to prevent more Chinese immigration to Canada (65).

Image Source:

“Keep the Chinese Out, Urges Labour Council.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 18 Jan. 1918: 5. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

1919

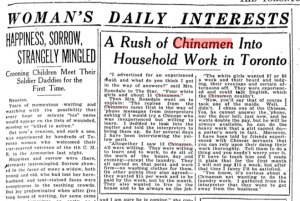

Post-War and Labour Fears

In 1919, with the First World War over, hostility against the Chinese increased as the Canadian economy dipped into a recession and war veterans were returning home unemployed and feared that their jobs were “being taken away by the Chinese” (Chan, The Chinese in Toronto from 1878, 66). In November that year, a mob of 400 men and boys stormed Elizabeth Street, looting and rioting against the Chinese community in reaction to an incident involving a soldier, which was perpetuated by the growing fear of Chinese labour (“Mob Raids Chinatown, Hour of Wild Riot,” 9).

Image Sources:

“A Rush of Chinamen Into Household Work in Toronto.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 20 Mar. 1919: 23. ProQuest. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“Mob Raids Chinatown, Hour of Wild Riot.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 18 Nov. 1919: 9. ProQuest. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

1920

Dominion Elections Act

In 1920, Chinese-Canadian war veterans were granted the right to vote, but they were unable to due to the Dominion Elections Act, which was introduced later that same year. The Act stated that the Chinese, including the war veterans, would be excluded from exercising the right to vote (Chan, The Chinese Community in Toronto, 74).

Image Source:

“Hon, W. L. M. King Flays Election Legislation.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 21 Aug. 1920: 5. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

1921

Head Tax at $500

Image Source:

“Head Tax Certificate for Chong Do Dang.” Digital image. The Early Chinese Canadians, 1858-1947. Library and Archives Canada, 16 Jan. 2009. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

1922

Chinese Segregation in Schools

Image Source:

Faculty and students pose in front of a Chinese Public School in Victoria BC. Photograph. Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. Chinese Canadian National Council, 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

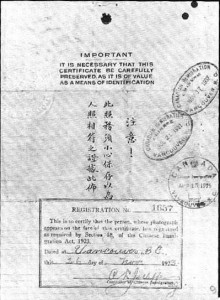

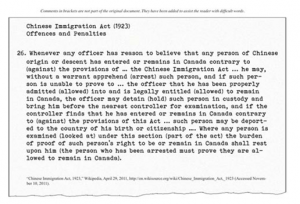

1923

Chinese Immigration Act passed

Image Sources:

Excerpts from the Offences and Penalties section of the Chinese Immigration Act. 1923. Digital image. “The Exclusion Act.” The Critical Thinking Consortium. 1 Jan. 2011. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

Registration Certificate. Digital image. Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. Chinese Canadian National Council, 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

1925

Death of Sun Yat-Sen

When the founder of the Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-Sen passed away, thousands of Chinese people filled the street as they marched to a funeral service at Victoria Hall. Sun Yat-Sen played a major role in the modern Chinese political history, by helping overthrow the monarchy in 1911-12.

Image Source:

“Sun Yat-sen.” Photograph. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 May 2015. Web. 30 June 2015.

1928

Chinese Cafes Can Hire White Waitresses

Prior to 1928, the Ontario government had restricted who could work at businesses owned by Chinese people. The law finally ended in 1928. According to the City archives, “the law addressed unfounded fears that Chinese employers would take advantage of white women.”

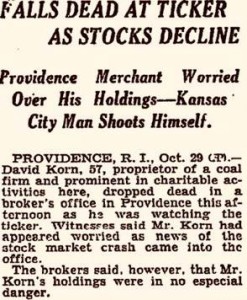

1929

Black Tuesday

Image Source:

“Falls Dead at Ticker as Stocks Decline.” The New York Times 30 Oct. 1929. Newsprint. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

1930

Chinatown in the Depression Years

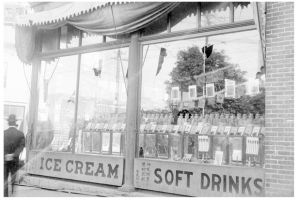

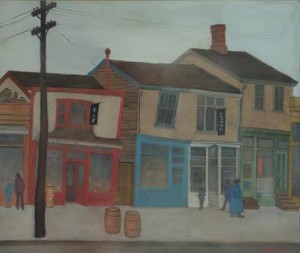

By 1930 Chinatowns across Canada were firmly established and well-defined communities containing shops, restaurants and various other businesses. The above image is of a Chinese shop taken in 1928. The shops would continue to be in business until the extreme decline of the Great Depression between 1928-1939.

Image Source:

Boyd, John. Chinese shop on Elizabeth Street, Toronto, Ontario. 6 Jan. 1928. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

1932

The Dirty Thirties

By 1932 the period that became known as the “dirty thirties” or the“hungry thirties” was established. Loss of businesses and homes (which were often in one building) due to the decline was prevalent in Chinatown. Less food and hand-me-downs were the norm.

Image Source:

A typical home and business combination at 60 and 62 Elizabeth Street (Series 372, subseries 33, item 251). 1937. City of Toronto Archives, Toronto. City of Toronto Archives. Web. 6 July 2015.

1933

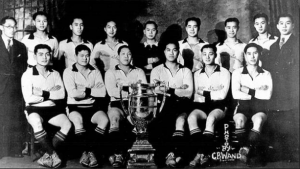

Chinese Students Soccer Team Become Provincial Champions

In 1933, when the Chinese Students Soccer team won the top trophy in the province with a thrilling 4-3 victory over a heavily favoured team from the University of B.C., Chinatown erupted in an outburst of firecrackers, parades and celebration, the likes of which were never seen before or since.

In the teeth of the Depression, with anti-Chinese feeling an ever-present fact of daily life, the second-class citizens of Chinatown finally had something to cheer about.” (Mickleburgh)

That same year, Joe Young (World Yo-Yo Champion) tours schools giving demonstrations and lessons to classrooms and students.

Image Sources:

Matthews, James Skitt. A man standing on a car demonstrating yoyo techniques for a Sun $100 YoYo Contest (reference code: AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-1922). 28 Mar. 1933. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

Mickleburgh, Rod “Nearly 70 Years On, An Act of Inclusion for Chinese Students Soccer Team.” The Globe and Mail 11 Jan. 2011. Web. 5 Mar. 2015.

1935

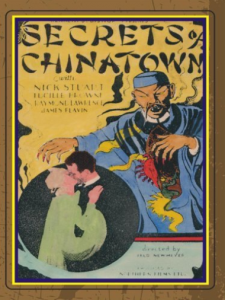

Chinese Images in Mainstream Media

The film, Captured in Chinatown, reflects the negative mainstream representations of the Chinese community in Canada and highlights the importance of the achievements above which provide the opportunity for more positive representations of this community to be presented to the public. Another film, Secrets of Chinatown, which also contains the stereotypical, negative depictions of the Chinese.

Image Sources:

“Captured in Chinatown.” Digital image. Movie Poster Shop. N.p., 1935. Web. 12 Mar. 2015.

“Secrets of Chinatown.” Digital image. The Internet Movie Database. IMDB.com, Inc, n.d. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

1937

The Second Sino-Japanese War

In 1937, Japan declared war against China, starting the Second Sino-Japanese war that lasted to the end of World War II. Members of Toronto’s Chinatown were always interested in war news and supporting the Chinese in China. This interest led to the founding of the Chinese Patriotic League of Ontario (1937). Located at 24 Elizabeth Street, the organization sent money to China to help the war effort.

Image Source:

24 Elizabeth Street (series 1317, item 379). 1937. City of Toronto Archives, Toronto. City of Toronto Archives. Web. 12 July 2015.

1938

Unity in Chinatown

As the war in China continued, it served to unite many Chinese people against a common enemy: the Japanese. This was clearly seen in Canada where two rival political groups, the Kuomintongs and the Cheekongtongs, ended their feud in order to focus on defeating the Japanese. With the ending of this rivalry, all of Chinatown’s efforts were put towards raising money for the war back home.

Image Source:

“Toronto Tongs Sheath Sword Chinese Unite against Japan.” The Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 18 Feb. 1938: 1. ProQuest. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

1939

World War II Begins

In this year, World War II breaks out in Europe and, as an ally of Britain and France, Canada joins the war effort. Large numbers of Chinese Canadians from across Canada volunteered to fight for their country. They served in all branches of the Canadian military and were seen as particularly useful in the Pacific theatre (Chinese Canadian Military Museum).

Image Source:

Wong, Frank. “Frank Wong in basic training. Vernon, British Columbia.” 1942. Photograph. The Memory Project. Web. 30 June 2015.

1940

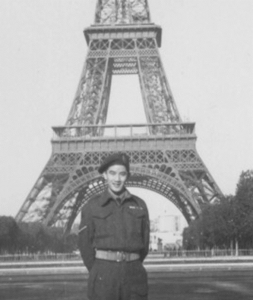

Chinese Canadians at War

As the Second World War continued, the number of Chinese Canadians that volunteered increased. Though the war had no end in sight, the soldiers fought bravely for their homes and eventually succeeded in winning the war. Though the air force and navy originally refused to accept Chinese Canadians, they eventually overturned this policy. This decision helped the war effort, both at home and abroad. (Chinese Canadian Military Museum)

Image Source:

Wong, Frank. “Frank Wong in front of the Eiffel Tower. Paris, France.” 1945. Photograph. The Memory Project. Web. 30 June 2015.

1941

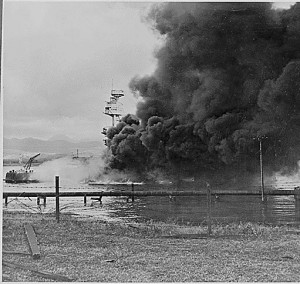

Bombing of Pearl Harbor

Dec 7, the Bombing of Pearl Harbor occurred. Roughly 8 hours after later, Hong Kong was invaded by Japanese soldiers. These two attacks inspired many Chinese-Canadians to defend both their heritage in China and their new life in Canada. This caused over 600 Chinese-Canadians to volunteer and this in turn started turning the gears of change that would lessen the racial tension between Chinese immigrants and settled Canadians.

Image Source:

Naval photograph documenting the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii which initiated US participation in World War II. 1941. Photograph. ibiblio. American National Archives. Web. 29 June 2015.

1942

Burma Campaign Begins

The Burma Campaign began this year, which was one of the first times Chinese and British (Canadian included) forces fought alongside each other. This would also be important to Chinese Canadians as there would be a need for British forces who could speak the languages of China.

Image Source:

The War in the Far East: The Burma Campaign 1941-1945. 1942. Imperial War Museums, Imphal. Imperial War Museum. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

1943

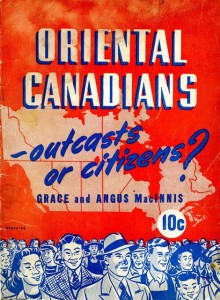

Changing Perspectives on the Chinese

In Canada, the beginnings of how Chinese immigrants were seen began to change. “Oriental Canadians -Outcasts or Citizens?” A booklet opposing discrimination against Asian populations in Canada was written by Grace and Angus McInnis, and was published in 1943. Both Grace and Angus were politicians who worked for the BC government.

Image Source:

MacInnis, Grace and Angus MacInnis. Oriental Canadians, Outcasts or Citizens?, Excerpt (4). 1943. Multicultural History Society of Ontario, Toronto. Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

1944

Conscription Crisis

Though D-day, marking the ending of the world war, would happen this year, So too would the Conscription Crisis of 1944. Though Canada’s volunteer numbers were dropping lower, and many of those conscripted refused to fight, many volunteer Chinese-Canadian soldiers were still stationed overseas. One of these soldiers was Victor E. Wong, who can be seen above in a portrait that was taken prior to him going overseas.

Image Source:

Portrait of Victor E. Wong. 1944. University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Victoria’s Chinatown. Comp. Charles Yang. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

1945

VJ Day

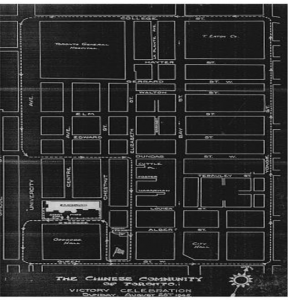

The celebration of V-J Day also known as “Victory over Japan Day” was declared on August 15th as allies announced the surrender of Japanese forces during WW2. The year was defined by victory as Japan surrendered and the Chinese finally, after enduring many years of discriminatory laws and biased representations of their culture, were able to join all other non-Chinese Torontonians/Canadians to celebrate. Celebrations included not only parades, but musical gatherings which filled the streets of Toronto. Both the Chinese and Canadians filled the streets until late into the night. The evening ended with fireworks.

Image Sources:

Lindsay, Jack. “Chinese Dragon in Victory Celebration Parade in Chinatown.” Aug. 1945. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

Lindsay, Jack. Chinese musicians playing during V.J. Day celebrations in Chinatown. Aug. 1945. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

Map of the specific route for the V-J day celebration parade. The parade started and ended on Armories. The Chinese in Toronto from 1878: From Outside to Inside the Circle. By Arlene Chan. Toronto: Dundurn, 2011: 94. Print.

1947

Progression of Rights

As the attitudes towards the Chinese began to finally change after WW2 there was much discussion about, and a push towards, the repeal of the Exclusion Act (1932) which prohibited immigration of the Chinese to Canada. The Act included many unjust restrictions placed upon the Chinese including a Head Tax in order to enter Canada. The Head Tax was initially set at $50 and rose to $500. The Head Tax prevented many Chinese from bringing their family over to Canada due to the lack of money earned for their jobs. After the Act was repealed in 1947, the Chinese were also given the right to vote.

Image Source:

Head tax certificate for Chong Do Dang. 11 Feb. 1922. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 6 July 2015.

1948

Lichee Gardens Opens

The opening of Lichee Gardens helped change the profile of Chinese restaurants in Toronto. Lichee Gardens was also part of the ‘Big Four’ restaurants that helped to attract non-Chinese to visit Chinatown and make it into a tourist attraction. Official recognition of the Chinese community after WW2 may have also helped popularize Lichee Gardens. Lichee Gardens was a massive successive and was open for many years. It attracted many non-Chinese Canadians to the area of Chinatown as the restaurant which helped in the growth of Chinatown and of the city of Toronto.

The restaurant moved to a number of locations, including the Atrium, Bay Street, Thornhill and King Street West; however, it always maintained its extensive menu which included some of their most famous specialities such as their spring rolls. The first owner of the restaurant was Henry Lam, who like other Chinese of his generation, had to pay the Head Tax when first coming to Canada.

Image Sources:

Lichee Garden from the 1970s. Comp. John Chuckman. Photograph. Chuckman’s Photos on WordPress. WordPress, 7 Sept. 2013. Web. 16 July 2015.

“Saving Chinatown.” The Chinese in Toronto from 1878. From outside to inside the circle. By Arlene Chan. Toronto: Dundurn, 2011: 108. Print.

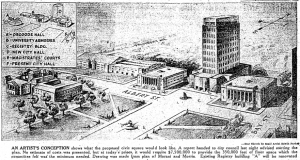

1952

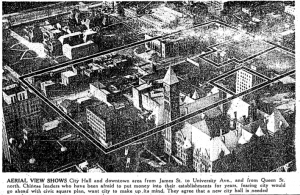

Toronto Plans a New Civic Square

Plans regarding a new civic square began. The original proposed concept for new city hall is very different from what we know today as Nathan Phillips Square, and through the various setbacks and deliberation that occurred in the development of new city hall, it is clear that the process was drawn out, causing tension among the Chinese community who were eventually driven out of Chinatown to make way for this city establishment.

As a result of the city’s desired location for a new city hall, the Chinese people knew that would have to vacate their homes, and move their businesses. However, due to the delay of the cities final decisions the Chinese people spent many years unsure whether to invest money in their homes and businesses due to the fear that they would soon be pushed out, thus losing more money than they would have if they had not invested in their properties.

The newspapers reported varied opinions of members of the Chinese community towards the plans for new city hall. While one Chinese citizen was reported as stating: “The city hall in now too crowded. A new one is needed. We have no objections” another Chinese citizen expressed frustration when he stated: “Because the city was going to someday take over the area, nobody else would buy property there. We who owned the property were afraid to put money into our own establishments to improve them, although we wanted to. We would go to the city hall and they would tell us it was our own business if we wanted to spend money on our property but they could give us no guarantee as to when the city would want the area.”

Image Sources:

Brehil, John. “Residents of Chinatown Happy About Civic Square, but Wish City Would Make Up Its Mind About Plan.” Toronto Daily Star 11 Dec. 1952: 3. Proquest. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

1953

Victory for Canada

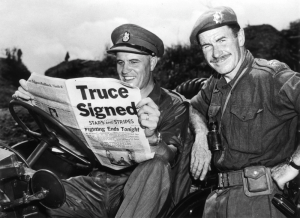

The end of the Korean War was one a relief for the Chinese-Canadian community in the 1950s. During this time period, Chinese were often lumped together with Koreans (they were all seen as “Orientals”) and Chinese often found themselves the targets of the hate and racism directed towards Koreans more generally. After the “victory” of the Korean War, much of this racist and anti-Asian propaganda stopped, making life for Chinese-Canadians a little easier. Additionally, many Chinese-Canadians fought and aided in the war effort with the Canadian Military, and a select few were awarded for bravery and valor.

Image Source:

“Korean Truce.” 2 Aug. 1953. Photograph. Hulton Archive. Getty Images, n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

1954

Hurricane Hazel

This photo is significant because it depicts a scene of the damage that was inflicted upon much of Toronto from Hurricane Hazel. Hurricane Hazel hit in the early Fall, and was particularly hard on those who did not have the money or means to re-build or move if their homes or businesses were damaged. Hurricane Hazel affected almost everyone in the city, and hit the poorest the hardest.

Image Source:

Baxter, Les. Hurricanes: Hazel 1954: No. 3 Folder. 1954. Toronto Telegram Fonds F0433, Toronto. York University Digital Library. Web. 29 June 2015.

1955

Businesses of Old Chinatown

500 people lost their jobs/businesses, and were given unfair compensation/payment for their businesses to accommodate the building of Toronto’s new City Hall. They were not allowed to re-open or move their businesses, the city simply took control of the land to make way for new City Hall. During this time frame of expropriation, business owners were given extremely short notice and next to no information as to what was happening. Business owners were told they had no choice – either they sold their business to the city or it would be forcibly taken from them and they would be charged/arrested. If charged/arrested, they would be given even less money for their business. This photo shows just a fraction of the business owners affected by the construction of new City Hall.

Image Source:

Chinese-Canadian business owners pose for a photograph in front of businesses at what is currently 1773 – 1779 Dundas Street West. 1955. City of Toronto Archives, Toronto. Chinese History in Toronto. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

1958

The Year of the Dog

In this photograph, Harry Lowe and Joe Young showcase a lion’s head with a multi-coloured train. The lion’s head represents a sign of good omen to those celebrating the Chinese New Year. The lion’s head was imported from Hong Kong to Toronto in preparation for the Chinese New Year being celebrated in Toronto’s Chinatown. According to the Chinese calendar, 1958 was the Year of the Dog.

Image Source:

“New Lion Head Arrives for Year of Dog Parade.” The Globe and Mail (1936-Current) 14 Feb. 1958: 4. ProQuest. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

1959

Chinatown Tours

This photograph festures Barbara Mark, Marg Ko, and Ruth Lor (Malloy) on the top row from left to right; and, on the bottom row from left to right, Eleanor Chu Wong and Louise Mark. These five Chinese-Canadian women participated in the tours of Chinatown that were being offered in 1959. They helped organize the event and a post-tour dinner as well. The money raised from these tours and dinners went to the United Appeal.

Image Source:

“Chinatown Tour, Toronto.” Photograph. Chinese Canadian Women 1923-1967. Multicultural History Society of Ontario, n.d. Web. 26 June 2015.

1960

Exploring Chinatown

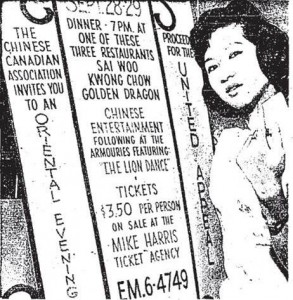

In 1960, The Toronto Daily Star covered the events of the extravagant ‘Evening in Chinatown’. The evening included dinner at a Chinese restaurant, tour of Chinatown, demonstration of oriental dances and music. Janis Jare (image on the left) performed a classical Chinese dance as part of the evenings performances. The event was designed for people who were not quite familiar with the Chinese traditions by giving them some exposure to various aspects of Chinese culture. The event was sponsored by the Chinese-Canadian Association and the proceeds went to the United Appeal.

This was not the only such event to occur in the 1960s. Other tours, including entertainment and dinner at restaurants like Sai Woo, Kwong Chow, and Golden Dragon, were also held. These events were also organized by the Chinese-Canadian Association in support of the United Appeal.

Image Sources:

“Janis Jare Performed a Chinese Classical Dance.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 29 Sept. 1960: 37. ProQuest. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

“Let Her Be Your Guide.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 22 Sept. 1960: 34. ProQuest. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

Whyte. Oriental Evening. 1960. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Toronto. Chinese Canadian Women 1923 – 1967. Web. 30 June 2015.

Acknowledgements

The students in Ryerson University’s ENG 390: Open Topics in Experiential Learning, winter 2015 class would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in helping with their research:

Arlene Chan

Val Lem

Valerie Mah

Contributors

Students in Ryerson University’s ENG 390: Open Topics in Experiential Learning, Winter 2015:

Beca, Daniella (1925 -1928)

Callahan, Nicole (1902 – 1905)

Dermott, Kendra (1913 – 1916)

Drmay, Sidney (1906 – 1909)

Etheridge, Kieran (1937 – 1940)

Ford, Christina (1933 – 1936)

Fralick, Kaitlyn (1898 – 1901)

Frazer, Roxanne (1929 – 1932)

Ilahie, Mona (1917 – 1920)

Khan, Aiman (1921 – 1924)

Larabie, Samantha (1894 – 1897)

Lopez, Rachael-Paige (1953 – 1957)

Marchitto, Megan (1886 – 1889)

Meyer, Annaliese (1949 – 1952)

Novais, Emil (1882 – 1885)

Rallis, Sidney (1878 – 1881)

Sellathurai, Abiramy (1958 – 1961)

Stickney, Brianna (1890 – 1893)

Venturo, Sarah (1945 – 1948)

Zacharko, Vincent (1941 – 1944)

Ziaee, Zuha (1910 – 1913)

Sources

“20 Taken When Police Make Midnight Raid.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 12 Nov. 1917: 5. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

24 Elizabeth Street (series 1317, item 379). 1937. City of Toronto Archives, Toronto. City of Toronto Archives. Web. 6 July 2015.

“A Rush of Chinamen Into Household Work in Toronto.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 20 Mar. 1919: 23. ProQuest. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“A Section of Yesterday’s Chinese Parade.” The Globe (1844-1936) 9 Jan. 1912: 1. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

A typical home and business combination at 60 and 62 Elizabeth Street (Series 372, subseries 33, item 251). 1937. City of Toronto Archives, Toronto. City of Toronto Archives. Web. 6 July 2015.

Abagond. “Chinese Americans in Mississippi under Jim Crow.” Abagond. WordPress, 12 June 2014. Web. 26 June 2015.

Advertisement Released around the time of Amendments to the Geary Act. The Internet Web Log of Jesse La Tour. Blogger, 27 Mar. 2013. Web. 6 July 2015.

“An Act Respecting and Restricting Chine[se] Immigration.” Early Canadiana Online. Early Canadiana Online, n.d. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

“An Act to Amend ‘The Chinese Immigration Act.’” 1987. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. Statutes of Canada, n.d. Web. 30 June 2015.

“Anti-Christian Comic Has a Moral (反洋教漫画 有寓意).” Cartoon. Shezhuzhanyang FIG (射 猪斩羊图). Historical Perspectives (历史大视野), 5 June 2015. Web. 6 July 2015.

Attestation Paper for Wee Hong Louie (AKA Walter Henry Louie). 1917. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Bateman, Chris. “This Is What Toronto Slums Used to Look Like.” blogTO. Tim Shore, 11 Sept. 2013. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Baxter, Les. Hurricanes: Hazel 1954: No. 3 folder. 1954. Toronto Telegram Fonds F0433, Toronto. York University Digital Library. Web. 29 June 2015.

Beasley, W. G. Japanese Imperialism, 1894-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987. Print

Bengough, John Wilson. Riding Into Power. 1886. McCord Museum, Montreal. McCord Museum. Web. 26 June 2015.

“Boxer Rebellion – Chinese History.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Boyd, John. Chinese Shop on Elizabeth Street, Toronto, Ontario. 6 Jan. 1928. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Brehil, John. “Residents of Chinatown Happy About Civic Square, but Wish City Would Make Up Its Mind About Plan.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 11 Dec. 1952: 3. Proquest. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Bengough, John Willson. Wong’s Dispute with the Canadian Government over Payment of a $50 Head Tax. Cartoon. The First Chinese American. Scott D. Seligman.Hong Kong University Press, n.d. Web. 30 June 2015.

Brooks, Ernest. The Chinese Labour Corps on the Western Front, 1916-1918. 12 Aug. 1917. Imperial War Museums. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

Brown, Robert Craig. “National Policy.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, 2 July 2006. Web. 8 Feb. 2006.

“But We Will Not Register.” Cartoon. “Gam Lee educates the Americans.” Kansas City Stories 1893. Kansas City Stories 1893, n.d. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Captured in Chinatown.” 1935. Film Poster. Movie Poster Shop. Web. 12 Mar. 2015.

“Certificate of Residence.” 1892. California Historical Society, San Francisco. Online Archive of California. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Certificate of Residence, 1894.” 1894. Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Kenneth E. Behring Center, Washington. Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Kenneth E. Behring Center. Web. 29 June 2015.

Chan, Arlene. The Chinese Community in Toronto: Then and Now. Toronto: Dundurn, 2013. Print.

Chan, Arlene. The Chinese in Toronto from 1878: From outside to inside the circle. Toronto: Dundurn, 2011. Print.

Chikanobu, Toyohara. The Great Victory of Japanese Troops in Land Warfare at Asan, Korea. 1 Jan. 1895. Digital Image. Wikimedia Commons. Chikanobu: The Artist’s Eye. Web. 29 June 2015.

“Chinatown History.” Toronto Chinatown. WYGK Publishing, n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2015.

“Chinatown: Then And Now.” Toronto Public Library. Toronto Public Library, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Chinatown Tour, Toronto. 1959. Photograph. Multicultural History Society of Ontario, Toronto. Chinese Canadian Women 1923-1967. Web. 26 June 2015.

“Chinatown – Visiting Aviatrix.” Photograph. Toronto Daily Star 10 Aug. 1936: 19. Web. 2 Mar. 2015.

“Chinese Avid for War News.” The Globe and Mail 31 July 1937: 13. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society. The Chinese Canadian Military Museum, n.d. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Chinese Canadians at the Mission School in Vancouver, B.C. in 1898. 1898. Vancouver Public Library, Vancouver. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Web. 30 June 2015.

“Chinese Exclusion.” Encyclopedia. American Eras, 1997. Web. 26 June 2015.

“Chinese Exclusion Act.” Road to Justice: The Legal Struggles for Equal Rights of Chinese Canadians. Metro Toronto Chinese and Southeast Asian Legal Clinic, 1 Jan. 2011. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“Chinese Head Tax.” Chinese Canadian Stories. University of British Columbia, n.d. Web. 5 Mar. 2015.

“Chinese History in Toronto.” City of Toronto Archives. City of Toronto, n.d. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“Chinese Labour Corps.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Chinese Residents on York Street after 1915. Photograph. Heroes of Confederation: Kamloops. The Kamloops Chinese Cultural Association, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

“Chinese with the Allies.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 6 June 1918: 4. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

Con, Harry, Ronald J. Con, Graham Johnson, Edgar Wickberg, and William E. Willmott. From China to Canada: a History of the Chinese Communities in Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982. Web. 29 June 2015.

Cotterell, A.T. “Illustrated Historical Atlas of the County of York.” 1 Apr. 1878. Map. Historical Maps of Toronto. Web. 26 June 2015.

“Christians in China being Tortured and Murdered During the Boxer Rebellion (1900).” Painting. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 6 July 2015.

Cumming, Carmen, and John Wilson Bengough. “Politics: The Seventies.” Sketches from a Young Country: The Images of Grip Magazine. Toronto: U of Toronto Incorporated, 1997: 73. Print.

“Details of overseas Chinese July 1 Commemoration (Vancouver) on July 1, 1923.” Chinese Daily Times 2 July 1924. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

Deville, Edouard. Chinese Workers’ Camp on the C.P.R. C-021990. 1886. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. The Critical Thinking Consortium. Web. 29 June 2015.

“Discrimination.” Negotiating Citizenship: The Chinese and South Asian Communities in Greater Victoria. The University of Victoria, 1 Jan. 2013. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

Dunn, William, and Linda West. “Newfoundland Joins Confederation.” Canada: A Country by Consent. Artistic Productions Limited, 1 Apr. 1993. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

Excerpts from the Offences and Penalties section of the Chinese Immigration Act. “The Exclusion Act.” The Critical Thinking Consortium. 1 Jan. 2011. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

Faculty and students pose in front of a Chinese Public School in Victoria BC. Photograph. Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. Chinese Canadian National Council, 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

“Falls Dead at Ticker as Stocks Decline.” The New York Times 30 Oct. 1929. Newsprint. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

Friesen, Joe. “Chinese Head-Tax Funds Clawed Back.” The Globe and Mail 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 30 June 2015.

“From a 5,000-Year-Old Racial Background Come These New Canadians.” Photograph. Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 2 July 1936: 34. Proquest. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

Georges, Eugenia, and Donna Gabaccia. “From The Other Side: Women, Gender, And Immigrant Life In The U.S. 1820- 1990.” International Migration Review 30.2 (1996): 603. Web. 29 June 2015.

Gilmour, Julie F. Trouble on Main Street: Mackenzie King, Reason, Race, and the 1907 Vancouver Riots. Toronto: Allan Lane, 2014. Print.

Godfrey, W. F. G. Elizabeth Street, 1931. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Toronto Public Library. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Head tax certificate for Chong Do Dang. 11 Feb. 1922. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada. Web. 6 July 2015.

Herald, North-China. The Anti-Foreign Riots in China in 1891: With an Appendix. 1892. Reprint. London: Forgotten Books, 2013. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Hon, W. L. M. King Flays Election Legislation.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 21 Aug. 1920: 5. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

Hongzhang, Li. Li Hongzhang State Visit to Canada. 1896. Photograph. China’s External Relations – A History. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 June 2015.

“Immigration History: Ethnic and Cultural Groups: Chinese.” Library and Archives Canada. Government of Canada, n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2015.

“Immigration Restriction Act 1901.” National Archives of Australia. Australian Government, 1901. Web. 9 Feb. 2015

“In the Chinese Parade.” The Globe (1844-1936) 9 Jan. 1912: 9. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

“Janis Jare Performed a Chinese Classical Dance.” Photograph. Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 29 Sept. 1960: 37. ProQuest. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

“Kamloops Chinese Freemasons.” Heroes of Confederation. Kamloops Chinese Cultural Association, 1 Jan. 2010. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

“Keep the Chinese Out, Urges Labour Council.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 18 Jan. 1918: 5. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

Keller, George F. “The Chinese Question Again.” The San Francisco Wasp 28 Feb. 1888. American Memory. Web. 29 June 2015.

Kenshin, Ozawa. Bakumatsu Meiji no Shashin. 1894. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 29 June 2015.

King, William Lyon Mackenzie. Royal Commission Appointed to Investigate into the Losses Sustained by the Chinese Population of Vancouver, B.C. on the Occasion of the Riots in that City. Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1908. Print.

King, William Lyon Mackenzie. The Need for the Supression of Opium Traffic in Canada. Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1908. Print.

“Korean Truce.” 2 Aug. 1953. Photograph. Hulton Archive. Getty Images, n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Lai, David Chuen-yan. Chinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1988. Print.

“Let Her Be Your Guide.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 22 Sept. 1960: 34. ProQuest. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

Lindsay, Jack. “Chinese Dragon in Victory Celebration Parade in Chinatown.” Aug. 1945. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

Lindsay, Jack. Chinese musicians playing during V.J. Day celebrations in Chinatown. Aug. 1945. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

Low, Jeff. “Then and Now: Old Chinatown.” Urban Toronto. Urban Toronto, 26 June 2012. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

Macintyre, A. Lorne. “War Fever Rages through Toronto Chinatown.” The Globe and Mail 19 Aug. 1937: 4. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

MacInnis, Grace and Angus MacInnis. Oriental Canadians, Outcasts or Citizens?, Excerpt (4). 1943. Multicultural History Society of Ontario, British Columbia. Multicultural History Society of Ontario. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

“Man With Big Key Heads Celestial Parade Today.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 8 Jan. 1912: 5. ProQuest. Web. 7 Feb. 2015.

Map of the specific route for the V-J day celebration parade. The parade started and ended on Armories. The Chinese in Toronto from 1878: From Outside to Inside the Circle. By Arlene Chan. Toronto: Dundurn, 2011: 94. Print.

Matthews, James Skitt, Major. A man standing on a car demonstrating yoyo techniques for a Sun $100 YoYo Contest (reference code: AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-1922). 28 Mar. 1933. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

Mickleburgh, Rod “Nearly 70 Years On, An Act of Inclusion for Chinese Students Soccer Team.” The Globe and Mail 11 Jan. 2011: A4. Web. 5 Mar. 2015.

“Mob Raids Chinatown, Hour of Wild Riot.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) Nov 18 1919: 9. ProQuest. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“Moments of Chinese Canadian History.” Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. Chinese Canadian National Council, 2015. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Nast, Thomas. Which Color is to be Tabooed Next?. 25 Mar. 1882. Harper’s Weekly, New York. Thomas Nast Cartoons. WordPress. Web. 30 June 2015.

Naval photograph documenting the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii which initiated US participation in World War II. 1941. ibiblio. American National Archives. Web. 29 June 2015.

“New Lion Head Arrives for Year of Dog Parade.” The Globe and Mail (1936-Current) 14 Feb 1958: 4. ProQuest. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

Paine, S. C. M. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. New York: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print

“Parliamentary Committees: Chinese Immigration.” The Globe (1844-1936) 25 April 2015: 4. Proquest. Web. 29 June 2015.

Pearson, Stephen. “1950s News, Events, Popular Culture and Prices.” The People History. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

Pickett, J. “Vancouver, British Columbia, Western Terminus Canadian Pacific Railway.” The Wayfarers Book Shop, 1 Jan. 2012. Web. 19 Mar. 2014.

Portrait of Victor E. Wong. 1944. University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Victoria’s Chinatown. Comp. Charles Yang. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

“Qing Dynasty (1892).” Digital Image. “Atlas of the People’s Republic of China.” Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia, 6 Mar. 2015. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Railway Construction.” Chinese Canadian Genealogy. Vancouver Public Library, 1 Jan. 2012. Web. 29 June 2015.

Registration Certificate. Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. Chinese Canadian National Council, 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

Russwurm, Lani. “Vancouver’s Yo-Yo History.” Vancouver Is Awesome. N.p., n.d. 5 Jun. 2013. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

Salmon, James Victor. Elizabeth St., Looking N. from N. of Queen St.W. 1955. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 Feb. 2015.

Salmon, James Victor. Knox Presbyterian Church (Opened 1909), Spadina Ave. W Side of Harbord St. 1956. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 Feb. 2015.

“Saving Chinatown.” The Chinese in Toronto from 1878. From Outside to Inside the Circle. By Arlene Chan. Toronto: Dundurn, 2011: 108. Print.

“Secrets of Chinatown.” The Internet Movie Database. IMDB.com, Inc, n.d. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

“Six Months in Jail for Versatile Chinaman.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 24 Dec 1917: 2. ProQuest. Web. 4 Feb. 2015.

Stanley, Timothy J. “John A. Macdonald’s Aryan Canada: Aboriginal Genocide and Chinese Exclusion.” Active History. WordPress, 7 Jan. 2015. Web. 29 June 2015.

Staples, Owen. Knox Presbyterian Church, Spadina Ave. W Side of Harbord St. 1910. Toronto Public Library, Toronto. Toronto Reference Library. Web. 3 March 2015.

Statues of Australia. Chinese Restrictions and Regulations Act, 1888. Victoria, Chapter 4. Web. 6 July 2015.

“Sun Yat-sen.” Photograph. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 May 2015. Web. 30 June 2015.

Tang, Tom and Binh Lu. Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. Chinese Canadian National Council, 1997. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

Taylor, Jen. “How did Chinatown Come To Be?” Keeping it Real-Estate. Toronto Star, 6 Apr. 2015. Web. 6 June 2015.

“Taxing the Chinese.” Road to Justice: The Legal Struggles for Equal Rights of Chinese Canadians. Metro Toronto Chinese and Southeast Asian Legal Clinic, n.d. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“The Canada Pacific.” The Chicago Daily Tribune 18 Feb. 1881: 5. Chicago Tribune Archives. Web. 29 June 2015.

“The Chinese In British Columbia.” The Globe (1844-1936) 26 Aug. 1878: 2. Proquest. Web. 29 June 2015.

“The Chinese Parade.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 9 Jan. 1912: 6. ProQuest. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

“The Chinese Poll Tax.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 12 Dec. 1900: 3. Proquest. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

“The Exclusion Act.” The Critical Thinking Consortium. Library and Archives Canada, 1 Jan. 2011. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

“The McCreary Act Passed.” San Francisco Call 17 Oct. 1893: 6. California Digital Newspaper Collection. Web. 29 June 2015.

The War in the Far East: The Burma Campaign 1941-1945. 1942. Imperial War Museums, Imphal. Imperial War Museum. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

“Toronto Tongs Sheath Sword Chinese Unite against Japan.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) 18 Feb. 1938: 1. ProQuest. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

VPL # 421; C.P.R. Wooden Bridge Over Skuzzy River. 1881. Vancouver Public Library, Vancouver. Canadian Pacific Railway Photograph Collection. Web. 29 June 2015.

Wang, Jiwu. “The Chinese Community’s Response to Protestant Missions Prior to the 1940s.” Canadian Ethnic Studies Journal 33.2 (2001): n. pag. JSTOR. Web. 29 June 2015.

Whyte. Oriental Evening. 1960. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Toronto. Chinese Canadian Women 1923 – 1967. Web. 30 June 2015.

Williams, Donn B.A. V.J. Day Chinese Dragon Parade. 14 Aug. 1945. City of Vancouver Archives, Vancouver. City of Vancouver Archives. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

Wong, Frank. “Frank Wong in basic training. Vernon, British Columbia.” Photograph. The Memory Project. 1942. Web. 30 June 2015.

Wong, Frank. “Frank Wong in front of the Eiffel Tower. Paris, France.” Photograph. The Memory Project. 1945. Web. 30 June 2015.

Zhoy, Yongming. Anti-Drug Crusades in Twentieth Century China: Nationalism, History, and State Building. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 1999. Print.